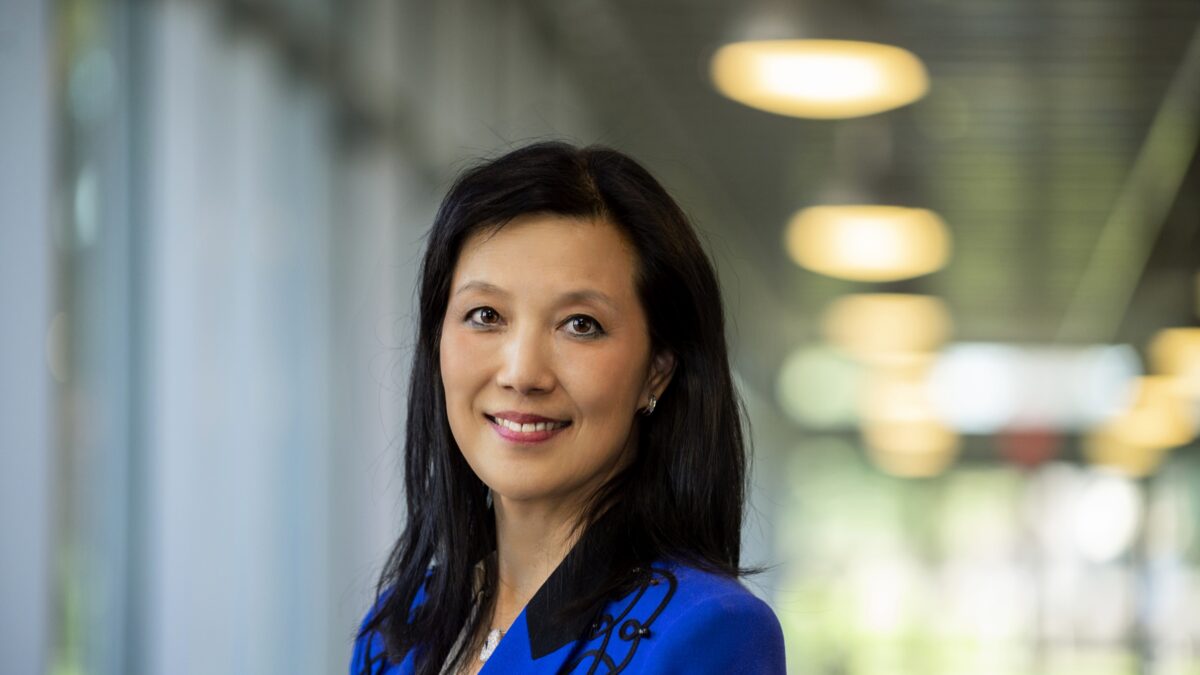

CEO Leadership Series: Jie Du, Ph.D., Former CEO & President, JDP Therapeutics Inc.

HOW TO SUCCEED WITH A PHARMA STARTUP WHEN YOU’RE ON YOUR OWN

Dr. Jie Du had a unique problem when it came to fundraising for her pharmaceutical startup—no one believed she did nearly everything herself to get the company off the ground. As a result, Dr. Du found herself funding the launch of JDP Therapeutics Inc., as well as the development and eventual FDA approval of its lead product, an injectable drug for acute allergic reactions, without any venture capitalist (VC) involvement.

Years of experience, as a research scientist in Big Pharma and in both science and business at a pivoting smaller company, gave Dr. Du the knowledge she needed to risk moving forward without VC backing. Her gamble and perseverance paid off—Dr. Du sold JDP Therapeutics to bring her drug to market in 2019.

In an interview with Ashton Tweed, Dr. Du explains why her business model confounded investors and gives advice to entrepreneurs having fundraising difficulties:

How did you transition from being a research scientist to becoming an entrepreneur?

In my early career, I was a research scientist at Abbott Laboratories and Merck. At that time, there was nothing on my mind except getting a job and doing good work—nothing about being an entrepreneur. A few years later, a recruiter convinced me to leave Big Pharma for a small company in Philadelphia, which at the time was a generic drug company. I started to have some involvement on the business side, especially intellectual property and patent litigation. Actually, since it was a small company, I ended up engaging in projects on both the science and business sides. I loved it much better than working in Big Pharma because previously I was only involved in one job function and not able to be involved in other areas.

Then the company changed its business strategy because of the low profit margin of generic drugs and switched to proprietary drugs. While I was the director of scientific affairs, the company began pursuing 505(b)(2) products, which is a regulatory term for products that use an existing molecule to develop into a new product with a new medical indication or dosage form. Nobody knew how to do that, but we learned on the job.

A lot of my business and patent experience came from the drug development of these 505(b)(2) products. It helped me understand the business and intellectual property in addition to being a drug developer. Eventually, this company was acquired and most of the scientists were laid off. I had to make a decision—should I look for another job or could I create other 505(b)2 drugs?

Because of the severance package I received, I decided to start my own company.

How exactly did you start building JDP Therapeutics?

To be honest, it’s all about developing a product. Since I was already a scientist and drug developer, I knew how to develop a drug, but I didn’t know what drug to develop.

I also knew I needed help on the business side, so I started going to business conferences in Philadelphia where I would network to meet professionals who could help me and provide that business side that I lacked.

I met Chris Cashman at a conference; he’s well known in the Philadelphia area. He was the CEO of Protez, which he had recently sold, when I met him. So, I asked him if he could help me with the business. That relationship really helped me nail down which drug to develop and the eventual successful exit of JDP.

How did you make that decision?

Chris asked me to do market research, so I talked with several physicians who made me realize that the three potential drugs I’d come up with didn’t really have good market needs. One of the physicians mentioned that the injectable acute allergic reaction space had no new drugs. There was only a drug called diphenhydramine, also known as Benadryl, which has been used as an injectable for acute allergic reactions since 1955. The lack of innovation in that space made me realize the unmet medical need.

The second step was to develop patent ideas to protect the product. This is really my forte—to come up with an idea, come up with a patent idea, and then start the FDA interaction. But, when I told this part to investors, they didn’t believe me because they’d never had anybody go to them saying, “I did this all myself.” Usually, a founder goes to an investor to raise money and says, “Okay, I’ve bought this technology, and hired this chief medical officer, etc., and a whole team.”

So, people really didn’t believe you did everything yourself?

No one took me seriously. I had such a big problem with investors because when they asked me—“Who came up with the clinical protocol? Who’s the inventor of the technology?”—and every answer was “I did it,” they didn’t believe me.

My story is much different from the majority of other startups because they usually have a business person/founder who hires a bunch of scientists to do the R&D work. I’m the opposite. I am the scientist. I did the R&D work myself, and I’m also the founder. So when I told people that I plan to do this, this, and this, and I already did this, this and that, and I wanted to submit to the FDA for approval, it was seen as not credible.

Is that why you didn’t rely on outside investors?

I actually approached around 150 investors and pharmaceutical companies to beg for funding or to out-license my product, but it was so unproductive. After being turned down again and again, I went to friends and family for investment. The good thing with friends and family is they don’t know the pharmaceutical industry, but they know me. So, they gave me the small initial investment; they invested in JDP simply because they trust me. In the end, because we did not have professional investor involvement like venture capital, these early angel investors received a return significantly higher than the industry norm.

Was there anything you were unable to do yourself?

The lab work. I couldn’t do that on my own so I had to contract with laboratories and manufacturing facilities. But when you contract with CROs, there’re always two parts. One is the actual work and one is the design work. The fees were cut in half because I did the designing piece myself.

What was the best decision that you made during this time?

I would say my best decision was at the beginning when I found a business person to help me. I think that’s one of the most important factors in JDP’s success. Another good decision was actually to turn down a VC’s term sheet that we received, whose terms were very unfair to my earlier investors. That was the most difficult decision I had to make, which later proved to be crucial to JDP’s success.

Would you recommend taking the route you’ve taken to other pharmaceutical startup founders?

Yes and no. I think if the founder is financially sound—meaning, if the founder is able to not take a paycheck from the company—they should do what I did. I worked for 10 years without pay, without taking any salary from the company. You have more control and you’re more productive because you don’t need to wait for seven board members’ approval. However all of the burden was on me. That might be too much for one person to bear. However, in my situation it was not my choice. I mainly was forced into that situation.

Why did you sell JDP when you did?

Once a drug is approved, you have to commercialize the drug. And for that we need a pharmaceutical sales team; JDP did not have that capability.

What are you currently doing?

I’m working for the acquiring company and we have signed on for another year to continue working together. I’m also focusing on philanthropy work. My earnings from the sale of JDP were significantly bigger than a typical founder’s because there was no VC involvement, so I want to give back to society. I recently donated $5 million to University of the Pacific, where I got my Ph.D., to found a drug development center at the university’s school of pharmacy.

Did being a woman add any challenges to launching JDP?

Yes. But for me, it’s not just being female, it’s being female and Chinese together that really made my life very difficult in fundraising. I did not have much success raising money from local investment groups or VCs in the U.S.—I had to go to China to raise money. I don’t think this is an issue anymore because the VCs who rejected me in the past are emailing me that when it’s time to start another company, they’re going invest.

What advice would you give an entrepreneur who’s having trouble raising funds?

First of all, you have to keep trying more investors. But, sometimes if you’re just not able to convince other people how good you are, you have to just go ahead and do it yourself—not just say it, do it. Once you complete the Phase II and III clinical trials or receive FDA approval, there’s nothing they can doubt.

If you’re a scientist like me, you need to find a business partner who can give you the business side of the pharma industry. And, your personal finances have to be strong, because if you live paycheck to paycheck, entrepreneurship is not for you. This is a hard thing for people to hear but, if I was not able to sustain myself that long, I would have given up.

Then, if you know your product is good, just believe in yourself and keep on going. The only thing that kept me going was my belief in this product and the product’s benefits for patient care over the current therapy. I also couldn’t stop because I took my friends and family’s money—I couldn’t let them down. I couldn’t tell them that I lost all their investment money.

Some of those early investors were my friends from church, and every time I went to church, they would ask, “How’s JDP doing?” I avoided church for three or four years. But I told them, “I don’t know how to answer you, but believe me, I’m going to give you a high return in the end.”

Ashton Tweed would like to thank Jie Du for this interview. If your company needs help from members of the Ashton Tweed Life Sciences Executive Talent Bank, we can supply that assistance either on an interim or a permanent basis. Additionally, if you are among the many life sciences professionals affected by the changes in the industry, Ashton Tweed can help you find the right placement opportunity — from product discovery through commercialization at leading life sciences companies — including interim executive positions and full-time placements. In either case, please email Ashton Tweed or call us at 610-725-0290. Ashton Tweed is pleased to continue to present insightful articles of interest to the industry.

Jie Du

Jie Du

Jie Du founded JDP Therapeutics Inc. and served as its CEO and President until JDP was acquired in 2019. Her previous positions include Director of Scientific Affairs at URL Pharma Inc., Senior Research Pharmacist at Merck, and Research Scientist at Abbott Laboratories. Dr. Du also co-founded Frontage Laboratories Inc. She earned a Ph.D. in Pharmaceutics at the University of the Pacific. Dr. Du lives in Lansdale, Pa., and enjoys ballroom dancing several times a week.

1 Comment

Great, inspirational story. Thanks for sharing.